Recently I was reading Cotillion, by Georgette Heyer, and—

OK. Half of you are saying, “Who’s Georgette Heyer?” and the other half are saying, “Hey, you’re male.” Time for a recap.

Georgette Heyer was an author—or, so I gather, the author—of regency romances in the middle of the 20th century. Regency romances are romance novels set in Regency England, in the time after George III went made but before his death. I do not usually read romance novels, but there’s something about Heyer, as authors as diverse as Lois McMaster Bujold and Julie Davis have noted. She’s funny, she has great characters, she writes well; and when you’re in the mood for something light and frothy, they are great fun. I suspect that she is more akin to P.G. Wodehouse (though less farcical) than to the average romance novelist. And it would be hard to overstate her influence. Some years back there was a flood of novels intended as sequels or companions to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and with the noted exception of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies the ones I glanced at all seemed to owe as much or more to Heyer as they did to Austen. She created her own fictional world, every bit as carefully constructed as a good science fiction or fantasy milieu, and millions have accepted it as the Real Thing. (Give her a try. Try Frederika. Or possibly Talisman Ring. Or maybe The Grand Sophy. I’ll wait.)

So anyway, I was reading Cotillion, in which a thirty-something man of property is travelling from London to the country to make an offer of marriage to a long-time acquaintance. He is not in love with her, or with anyone, but he’s the heir and it has been successfully impressed upon him that he must marry. He well likes his long-time friend, and so off he goes. On the way, he encounters a young woman of good family, great spirit, equal beauty, and little experience who is running away from home because her grandfather, the patriarch, won’t let her marry the man she wants to marry, because she is too young. What’s a gentleman to do? She has a grand strategy, but he can see it won’t answer. He can’t take her back to her family, because she won’t tell him who they are. He can’t leave her on her own; there are unscrupulous people about, don’t you know. Got to take her with him. And from there, of course, the tangles increase.

Now, here’s what led me to reflection. All of his acquaintance are wondering what has happened to him. They hear about the girl, and they all begin to jump to conclusions. Long, drawn out, extremely logical, plausible, believable conclusions, all of which happen to be quite wrong; and they go wrong for two reasons: first, they don’t have all of the information; and some of the information they do have they disbelieve. But as I say, their conclusions are, given the information they have and choose to believe, completely logical.

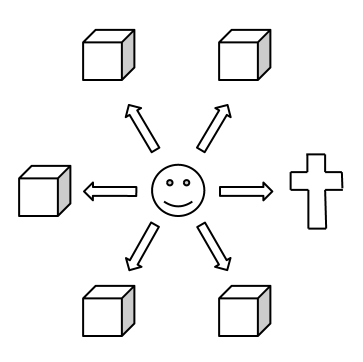

It occurred to me that we are in much the same position relative to God. It is possible (see Thomas Aquinas) to deduce the existence of God from first principles; and given that He exists, there are certain things that can proven about Him: that He is omnipotent and omniscient, for example. But is less obvious is that these statements are essentially negative. God is infinite, you see, not in the mathematical sense, but in the sense of being unbounded. We can put no bounds on His knowledge or His power. That doesn’t mean that we truly understand what it means to be omnipotent; we don’t. It is simply not conceivable to us.

And yet, on a daily basis we try to make sense of God, and thus to put bounds on Him. And perhaps we even reason logically, and come to valid conclusions, based on what we know for sure. But the one thing we can know for certain sure is that God eludes our intellectual grasp. This why Pope Benedict in his writings frequently refers to God as the “Wholly Other”.

And yet, all is not lost. We are doomed to intellectual failure, but we are not doomed altogether.

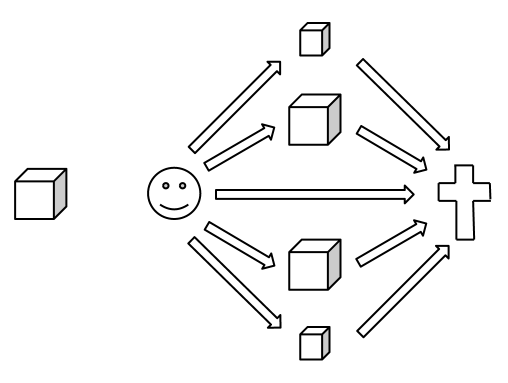

We cannot grasp God, not intellectually, and certainly not by reasoning from first principles. But He knows this, and He doesn’t leave us orphaned. Instead, He has revealed Himself to us, first through His history with the Israelites, and then in the person of Jesus Christ. He’s in fact told us quite a lot about Himself, and all we really need. It’s partial information, but it’s enough.

Of course, we still go astray intellectually, just as the various on-lookers in Cotillion do. But the confusion does not go on forever. In time the gentleman comes home, and the on-lookers are able to find out from him what’s really been going on. And so we can go to God; and so in time He’ll bring us to live with Him, we are allowed to hope, and we will see Him clearly, and all our questions will be answered.

As I promised, I’m now going to go into some detail about how combat works in

As I promised, I’m now going to go into some detail about how combat works in